The Snake River is Jackson's largest gravel-bed river ecosystem

This means the Snake River doesn’t just flow down the visible river channel. It flows over and through the entire floodplain system, from valley wall to valley wall, and supports an extraordinary diversity of life. See below for sources.

An Invisible River: most of the water in the Snake River is not in the river — it’s in the gravel.

A gravel-bed river doesn’t just flow down the channel. It flows over and through the entire flood plain system, from valley wall to valley wall.

Read MoreMelting snow and surface water flow down the channel; this is what we think of as a “river.” But underground, far more water is moving slowly through a labyrinthine network of cobble, gravel and sand that make up the entire valley bottom.

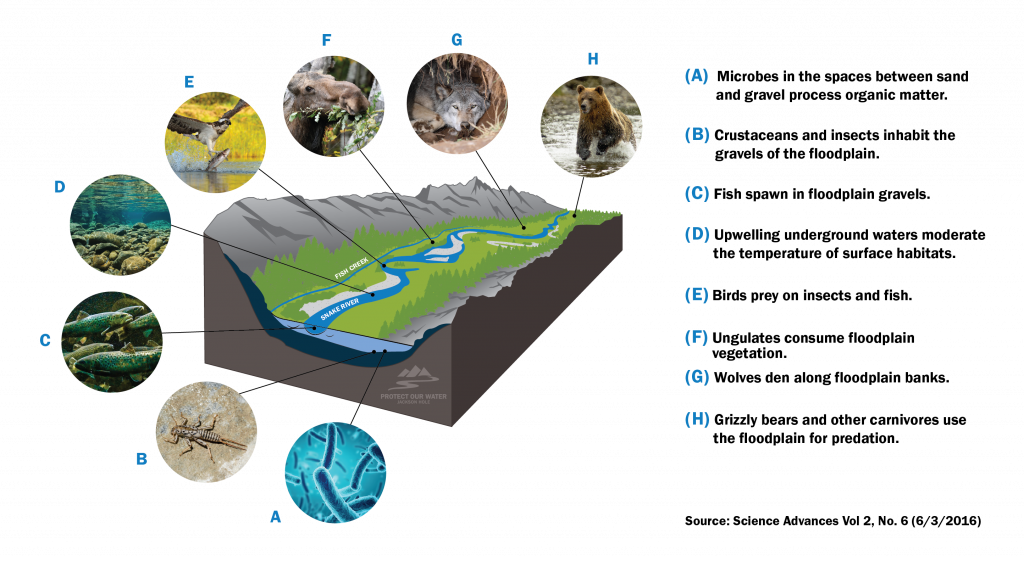

From Bugs to Bears, everyone relies on gravel-bed river ecosystems

A large number of species rely heavily on the biodiversity generated by the gravel-bed river ecosystem of the Snake River, not just fish and other aquatic species.

Read MoreGravel-bed river floodplains like the Snake River ecosystem are among the most ecologically important habitats on the continent. Their subterranean habitat is the foundation of a food chain that creates biodiversity in the entire valley, by nourishing microbes and aquatic insects, and plant life such as willows, cottonwood, and aspen, which in turn sustain fish, birds and beavers, elk and caribou, and consequently wolves and grizzly bears.

- Research has highlighted the importance of these gravel-bed rivers to an unexpectedly high proportion of the region’s aquatic, avian, and terrestrial species.

- Although river floodplains themselves make up only roughly 3 percent of many river valleys, two-thirds of all species spend part of their lives in the floodplain.

- Underground floodplains are the foundation of a healthy river “immune system”.

Human activities contribute to the weakening of the immune systems of rivers like the Snake

Although gravel-bed river floodplains play a large role in sustaining native plant and animal biodiversity, they have been disproportionately affected by human infrastructure and activities.

Read More- The impact of human development on top of our invisible rivers includes severe impacts to floodplain habitat diversity and productivity, restrict local and regional connectivity, and reduce the resilience of both aquatic and terrestrial species, including adaptation to climate change.

- Human river valley developments such as homebuilding, dam construction, irrigation, and channelization may be slowly choking highly dynamic river systems — and the biodiversity that depends on them — to death.

Nutrient pollution greatly affects Invisible Rivers

Interaction between surface water in the river and groundwater is fundamental to the health of the gravel-bed river ecosystem.

Read MoreNutrient pollution issues affecting our water quality, such as septic systems on the valley floor and using groundwater to dilute pollutants, affect the health of the entire floodplain immune system.

- Nutrient pollution alters the foundation of the ecosystem – microbes, aquatic insects, and riparian vegetation. The health of this foundation can have repercussions up the entire food chain within a gravel-bed river ecosystem.

- These harmful effects — coupled with reduced water flows from climate change, longer summers, and warmer water and air temperatures — are greatly diminishing the resilience of gravel-bed rivers, like the Snake River in Jackson Hole.